Q&A: Muslim Fashion by Reina Lewis

Earlier this month, Nadiya Hussain won Great British Bake Off; in September, Mariah Idrissi becomes the first model to wear a hijab in an H&M campaign: both instances of strong, beautiful women being recognised for what they had achieved. Yet there is another reading available: that both represented high profile revolutions in the way Western society perceives women in hijab - revolutions, in an age of increased racial and religious suspicion, that are timely and much needed.

Earlier this month, Nadiya Hussain won Great British Bake Off; in September, Mariah Idrissi becomes the first model to wear a hijab in an H&M campaign: both instances of strong, beautiful women being recognised for what they had achieved. Yet there is another reading available: that both represented high profile revolutions in the way Western society perceives women in hijab - revolutions, in an age of increased racial and religious suspicion, that are timely and much needed.

It couldn’t be a better moment, then, for the launch of Muslim Fashion, the latest work by Reina Lewis, Professor of Cultural Studies at London College of Fashion. Inspired by hip twenty-somethings hijabis, Muslim Fashion is a thorough and thoughtful study of what it means to be a hijabi in a time and place where religion, politics, ethnicity, class, gender, generation and nationality meet and potentially clash.

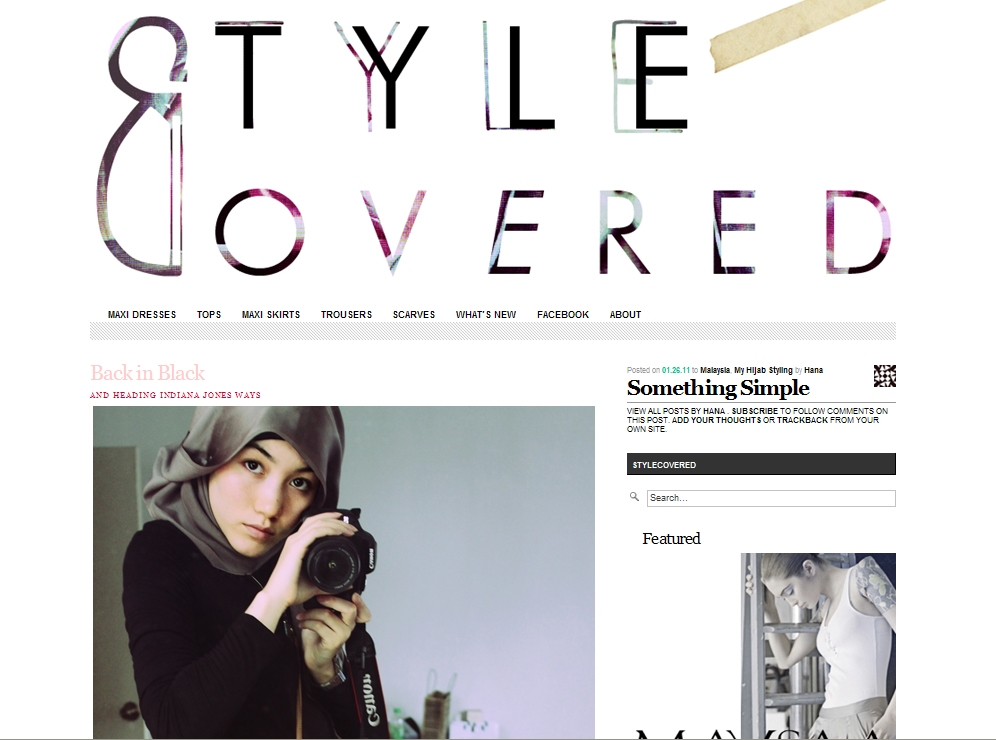

Participating in popular mainstream fashion, contemporary young hijabis are part of an emerging subculture that crosses faiths and borders. It’s quiet but it’s there. Witness the efforts of prominent brands: DKNY and Mango launched Ramadan collections in their Arab-based stores; net-a-porter.com offered an Eid Edit. Earlier this year, Liberty London invited Dina Tokio, arguably the most high profile hijabi blogger in the UK, to create looks with her favourite Liberty scarves and top blogger Hana Tajima created a capsule collection for Uniqlo that adhered to the Islamic guidelines for dressing.

‘The mainstream image of the everyday Muslim woman has largely been negative,' Tajima told Fortune magazine at the time. 'But it's shifting as she works to reduce the dissonance that exists between her — a woman who reads John Steinbeck and eats pizza — and “her” — a foreign figure of repression and ritual.’

Lewis' work is another, important voice in this chorus. In treating hijab as fashion, Lewis counters the use of images of veiled women as “evidence” that Muslims and Islam are incompatible with Western modernity and offers another, richer view of women in veils.

Bel: What were your aims in writing the book? Reina: My previous work was about Orientalism in literature and the fine arts and the ways in which the West had stereotypical, often negative attitudes towards the Muslim world. I wrote about the idea of the mystery behind the veil, how the image of the ‘Oriental woman’ was either oppressed and passive or overly sexual and tempting. After 9/11, I noticed more and more Muslim women wearing hijab, partly as a response to anti-Muslim prejudice. That’s been renewed each time - in London after the bombs of 2005, 7/7, and then after each perceived moral panic about Muslims as potential terrorists. So we’ve seen more Muslim women wearing the hijab but we don’t see this represented in fashion media. What I wanted to point out was that this is a phenomenon in British fashion but that it’s not included in celebrations of British street style.

Bel: Why is that important? Reina: Because this is a style phenomenon, a youth subculture that deserves attention. When I reach out to Muslim designers or bloggers, they’re understandably hesitant to speak to me because there’s so much prejudice. I’m not against the hijab, but neither am I advocating it. I see that this is happening in a different way with a younger generation who are choosing to cover, but they are choosing to do so through mainstream fashion.

Bel: How? Reina: They might wear so-called ethnic clothing for family events or when they go to the mosque. But mostly, they’re shopping on the high street. They’re operating through multiple fashion systems and the style media should pay attention to this. Maria Idrissi appearing in the H&M campaign is a massive moment. I’m getting emailed by everyone I’ve ever spoken to in the Muslim fashion world saying ‘have you seen this, this is incredible!’ And she’s a fantastic young woman; she is so calm and together and, of course, she is herself part of this growing niche market for religious or religio-ethnic-related fashion. She runs a salon that provides Moroccan henna and halal manicures.

Bel: Under-representation of certain groups is common in fashion but the issues around the hijab are even more complex ... Reina: One of the things I often say to women is ‘you’re not the only group that’s under-served by the fashion industry.’ Try being a fat teenager or a woman over 60! Over the last ten years, brands or retailers have often been anxious about interacting with Muslims, partly because of an anxiety that they might be associating the brand with a group that is seen by some as a security risk – but also because the cultural cringe when it comes to religion is even more pronounced than about ethnicity. People are worried they’re going to offend people. What’s important to point out is that there are multiple interpretations. Some Muslim women may well dress with modesty in mind - so they might wear a shirt undone to here, but not to here - but don’t feel the necessity to cover their heads. And women who do cover, cover in a variety of ways.

Bel: Within Muslim communities, there are different interpretations of what a woman should wear. Reina: There are a lot of nuances. While many of these young hijabis face surveillance outside the Muslim community, they can also face surveillance within the community. What’s important is that in non-Muslim-majority countries, most of the young women I’ve spoken to use a discourse of choice. They’ve chosen to do this and they want to make that point because so often people look at them and think they’ve been forced. That sense of choice is as much a part of a spiritual development as an individual journey - that’s true for a lot of young people, regardless of religion - and it extends to respecting the choices of other women, whether they cover or not, or how they cover. The other thing these women will say is that it’s just as wrong to compel someone to cover as to compel them to uncover. If girls are wearing hijab because their parents make them, that’s wrong. That emphasis on individual choice is very much a part of being of the West. For many, it’s about seeing Islam as a religion that guarantees human rights as individual rights.

Bel: Nadiya winning Bake-Off: what did this mean? Reina: It was glorious. She’s an incredibly good speaker. At the end, she said I’m never going to say I can’t do something again. You could bottle this and sell it; she’s amazing. She’s a Muslim but the program was about what she did, not what she wore. All this focus on what Muslim women wear takes away from what Muslim women actually do and what the real priorities are if we’re going to advance their social participation. So Nadia is a great poster girl, as is Maria. This was a campaign that had people who displayed diversity of all sorts: of age, of size, of ability, of visible ethnicity, of faith, because they had Pardeep as well and other Sikh men. So this is really one of the first times that we’ve seen religion included among the range of social diversity. And that’s very important.

Bel: Who are good models of young hijab fashion? Reina: There’s loads. I’ve interviewed a number of these young women and they’re so smart. What’s impressive is the blogger support and solidarity within faith groups. Established bloggers will help out people who are starting out. The ones leading the way are blogger Dina Tokio, Hijablicious, Nabiilabee who has an enormous following. Winnie Detwa in the States is incredibly smart and makes really cogent points. What’s interesting about blogging is you can read it around the world. You can communicate across language barriers so people can have enormous influence globally.

Bel: The fundamental issues are tolerance and diversity and individual choices … Reina: It is. I have so much respect for the women I’ve spoken to. Many of them are part of the progressive wing of religious communities that are sometimes quite conservative. Politically, it’s important to de-exceptionalize young Muslims - to say that, in many ways, they’re very much like everybody else and, in some ways, they’re particular – and for society to recognise these young women as potential future leaders.

Bel: Because these are women who’ve had to forge responses to very unique dilemmas. Reina: Yes, exactly! Some of these Muslim bloggers are Caucasian, some of them are converts, some are Afro-Caribbean, some of them are South Asian. And they’re facing particular challenges and they’re doing a really good job.